Rohit Dhankar

A participant (not mentioning name because I have not taken permission) in Nyaya-sah-adyayan WhatsApp group wrote the following:

- I have a question (and believe me I have no mischief in mind) where is this knowledge (knowledge of Nyay Darshan) going to benefit us in our practical (day to day) life and how?

- Why should a learner invest time and money on it?

- I am an Educator (if not an Educationist) and my main “Business is to do workshops for Teacher’s motivation, Teacher’s commitment, teachers’ style of teaching (let’s call it teaching methodology) and to a little extent ‘Pedagogy’.

- So how a person like me is going to get benefitted by this new knowledge?

My response

My response is as follows and believe me I do not interpret it as mischief and responding without any mischief in my mind.

The short answer:

“No benefit. And one who sees no benefit should not waste effort, energy and money”.

Long answer: (be patient and read):

An understanding of nature of knowledge is central to an educator. Education is primarily concerned with acquisition, creation, critiquing, examining, and using knowledge. The questions of “what is knowledge?”, “How it is generated?”, “How is it examined?” etc. are of fundamental importance for an educator. One hardly needs to argue that knowledge is required in all human actions. Vatsyayana claims right in the beginning of his Nyaya-Bhashya:

“Successful activity (samartha-pravrtti) results when the object (artha) is cognised by the ‘instrument of valid knowledge’ (pramäna). Hence the instrument of valid knowledge is invariably connected with the object (arthavat).

There is no cognition (pratipatti) of object (artha) without the instrument of ‘Valid knowledge’; without cognition of object there is no successful activity. On being aware of the object with the help of the instrument of knowledge, the knower wants either to get it or avoid it. His specific effort (samiha), prompted by the desire of either getting or avoiding (the object), is called activity (pravrtti), whose success (samarthya), again, lies in its invariable connection with the result (phala).”

Plato in Theaetetus 201c–201d (Translation: Benjamin Jowett) claims:

“For true opinions, as long as they remain, are a fine thing and all they accomplish is good; but they are not willing to remain long, and they escape from a man’s mind, so that they are not worth much until one ties them down by an account (logon): and this, my friend, is recollection. When they are tied down, in the first place they become knowledge, and then they remain in place. That is why knowledge is more honourable and excellent than right opinion: because bound by reason.”

Before coming to this passage Plato (Socrates in the dialogue) is talking about uses of true opinion in achieving one’s ends. Vatsyayana is making the same point. Umpteen number of philosophers are making the same point again and again. In common day-to-day activities of life we use knowledge all the time. Even in making a cup of tea one uses knowledge of heat, how to control the source of heat, how long water needs to be boiled, how much tea leaves and sugar, and so on. The success of making good tea depends on all this knowledge.

Vatsyayana says true cognition or knowledge depends on pramans, Plato says it requires reasons. In day-to-day life we seek grounds for accepting any piece of information; even if it is as mundane as what is the market rate of wheat today. Enquiry about grounds is to assure ourselves that the information provided is reliable; it is asking pramanas or reasons. Thus, knowledge and reasons behind it are of utmost importance.

Now there are two questions: 1. Is there unanimity in matters of knowledge and acceptable reasons or pramanas or methos? And 2. Do I want to be autonomous in deciding matters of knowledge or want to live on borrowed knowledge? The first one is concerned with having at the least reasonable grounding in understanding knowledge; and the second one about my autonomy as a human being.

There are multiple systems of epistemology, the discipline which discusses knowledge. They all have strong agreements on some points and equally strong disagreements on some others. They give different definitions, criteria and methods of examination of knowledge, and persepctives. If a teacher knows about more than one such systems s/he is more likely to think critically and clearly; and also, to be able to help her/his students in the same.

Nyaya is an alternative way of looking at knowledge to the generally studied western epistemology. It has a particular penchant for clarity and precision, defining and then examining propositions. It has developed ways of elaborating arguments and communicating to others. These ideas and methos add to our understanding of knowledge and its ways, often provide criteria to critically examine concepts and claims made in the western epistemology, and provide substance to be examined through the ideas and methods of western epistemology. Thus, depend and broadens our perspective.

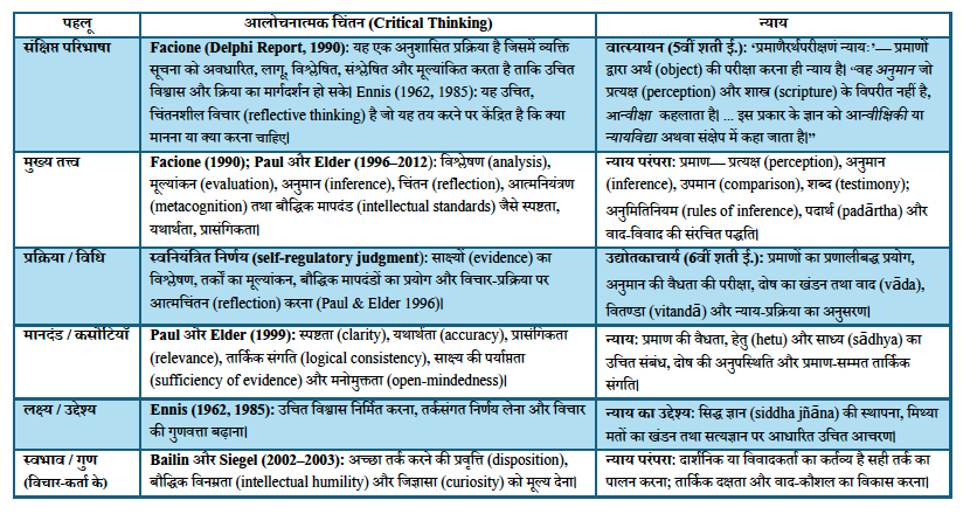

This should help one develop critical thinking, so much praised these days without really understanding what exactly it might be. The table below gives a tentative comparison between Nyaya’s ways of knowing and critical thinking, put forward more as an exercise in thinking than as a final conclusion. I do not have time to translate it into English, thus copying here in Hindi as it is:

One can go on and on on this issue. To the participants in this study I would say: better collect all the fliers posted as advertisements which duped you into this course to waste your money and time, and examine those numbered 1, 2 and 4. Also read again the introductory text given for the sah-adhyayan, right in the first session.

Can it help in, say, improving teaching methodology? Depends on (1) how well one understands Nyaya, (2) how well connected and consciously guided by theory his/her methodology is, (3) how conscious s/he is about having proper reasons for whatever she does in the classroom. To an activity cruncher and ready-made solution seeker it can give absolutely no help. To a conscious autonomous teacher it should. But, remember being autonomous is painful and dangerous.

Example 1: We all talk about leaving 2–5-year-old children much time for free exploration and play. Why do we recommend that? Common half understood answer is “children learn through play”. This is a mugged-up sentence which most of those who often repeat it cannot explain if one asks: what do they learn? How do you know? What is the use of what they learn? In western epistemology the idea of Knowledge by acquaintance gives one theoretical vocabulary and understanding of how sensory experience is basis of all knowledge and how it is connected with later development of skills and Propositional Knowledge. Similarly, understanding of Indriyas, their role in pratyaksha, the relationship between pratyaksha->sansakar->pramanas provides ability to articulate and think about those reasons. Which should help is choosing right kind of ‘free exploration’ for children at different stages of development. Aurobindo’s emphasis on sharpening sensory equipment for development of ideas and intelligence seems to come more or less directly from his understanding of indriyas and manas, and their role in knowledge formation.

Example 2: The understanding of anumana and difference between swartha and parartha anuman should directly help in spotting students’ difficulties in understanding as well as one’s articulation of explanation. But that we can understand when first we have studied anumana.

One can multiply these example with more detail and clarity, and we will do that in the course of this study as we progress. But at this stage, hardly having studied five concepts of Nyaya one should not attempt that.

But who can draw these benefits from studying Nyaya?

Anyone who puts in efforts and tries to understand. All efforts of using one’s mind and reason seriously even on completely unjustified and patently wrong disciplines will necessarily result in discipline of mind, rigorous use of logic, proper ways of reasoning and systematic thinking. I claim that serious and deep study of even astrology and palmistry will result in these “benefits of mind”, even if no “benefits of content”. However, many people do not understand the value of “benefits of mind”, one can see an example in Gandhi’s claim that study of geometry, astronomy, and geography helped him in nothing. (Hind Swaraj, chapter XVIII)

For whom will it be difficult to gain anything useful?

Let me begin by quoting Winch (last chapter in his Philosophy of Human Learning): “If one does not respect what one is to learn, or recognise the efforts that have gone into its creation and development, then success is unlikely.” Thus, attempts to study Nyaya (or anything) with a disdain for it will almost never result in good understanding of the subject and without good understanding its benefits will remain elusive. But “respect” here does not require an assumption of its truth or its benefits etc. in advance. All it requires is suspension of the judgment that “it is useless” or that “it is of great use” or that “I can understand whether X is useful without first knowing X”. Which means one has to enter with an open mind, with patience to draw a conclusion when one has learnt enough. A child who first wants to know the benefits of learning counting without knowing counting will never calculate even the area of his room.

Drawing benefits from study of Nyaya or anything written in Sanskrit centuries ago is very difficult without first studying it. Even its proper study is very difficult due to biases created by our education system. Anything written in Sanskrit is seen as archaic, or ponga-panthi or stone-age creation without knowing it. People will find tvak (त्वक्) as stone age without knowing that ‘touch’ comes from tvak or at the least has the same stone-age root. This disdain will strop proper and fair understanding, exactly as over-whelming respect or bhaktibhav will stop proper examination. Thus, entering into it with balanced open mind, open eyes and remanning patient till one has sufficient information to base one’s conclusions on is the key.

To re-emphasize the point: one cannot understand usefulness of a branch of knowledge without knowing what it happens to be. Yes, by asking others whom one believes or by asking a guru one can make an opinion about usefulness of anything. But that is more of an assurance at the best and indoctrination at the worst; not ‘understanding proper’. And that is why there is a contradiction between my “short answer” and “long answer”. Without knowing X, it is not possible to explain usefulness of X.

That is why the Sanskrit people had this concept of ‘Anubandh Chatushthay’ if you remember. They want to talk about the subject of a shatra, then relationship of the book wirth that Shastra, then prayojan of it’s study and then of being Adhikari. That may motivate people to study it. If one does not see prayojan one will find no inclination to study it. So, think if you have a prayojana which may be helped by this.

Posted by Rohit Dhankar

Posted by Rohit Dhankar